Looking Back at the 1918 Pandemic in Cleveland

Just over one century ago, the 1918 pandemic—better known as the Spanish Flu—ravaged the globe. An estimated 500 million people, or one-third of the world’s population, became infected with the virus between 1918 and 1920. Tens of millions of people around the world were killed within the span of several months.

As our nation struggles to come to terms with the “new normal” during the time of COVID-19, we are reflecting back on the lessons learned during the Spanish Flu outbreak. Below, we outline the history of the 1918 pandemic in Cleveland and provide an objective comparison to the novel coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

Timeline of the 1918 Pandemic

Though the true origins of the Spanish Flu remain contested, many researchers have theorized that a UK military camp in Étaples, France was the starting point of the virus. Other experts believe that the pandemic began in the United States. In either case, the rapid spread of the virus was undoubtedly tied to World War I activity in Europe and North America.

The first identified patients in the United States were military personnel in spring of 1918. Many U.S. soldiers were weakened by malnourishment and chemical attacks, leaving them vulnerable to respiratory illness. Overcrowded military hospitals created the perfect conditions for the virus to spread like wildfire.

Throughout the spring, U.S. soldiers and civilians alike rapidly became infected with the Spanish Flu. However, this initial wave of the virus was so mild that many doctors hesitated to refer to it as “influenza” in the first place. Complications were extremely rare, and the duration of the illness was short among the majority of patients.

By autumn 1918, a second wave of the virus swept across the nation—and this time, the illness would prove to be significantly more deadly. Symptoms were so severe that patients were often mistakenly diagnosed with typhoid or dengue fever rather than influenza. The northeastern United States became a hotbed for the virus, particularly transportation hubs like Boston and New York.

The 1918 pandemic was unprecedented in the sense that the majority of those affected were young, healthy adults. Roughly 99% of deaths in the United States occurred in patients younger than 65 years old, and close to 50% of deaths occurred in those between the ages of 20 and 40 years old.

U.S. Response to the 1918 Pandemic

Throughout the United States, local governments responded to the pandemic in exceedingly different ways. With no vaccine or treatment for the virus, physicians used every tool at their disposal to care for patients. Ultimately, non-pharmaceutical tactics—such as physical isolation and good personal hygiene—proved to be the most reliable and effective measures for preventing new infections.

Unfortunately, limitations on public gatherings were not applied evenly across the nation. For instance, Philadalphia opted to move forward with hosting its “Liberty Loan” parade in September 1918, during the height of the virus’s second wave. Some 200,000 citizens gathered in the streets of Philadelphia to celebrate and march.

The result of that decision? Within 72 hours of the infamous parade, every bed in the city’s 31 hospitals was filled. Week after week, the death count grew by the thousands. Morgues soon became overwhelmed by the number of bodies, and by mid-October local cemeteries had begun digging mass graves. By the end of the 1918 pandemic, more than 15,000 Philadelphians had lost their lives to the Spanish Flu.

Other cities hit particularly hard during the 1918 pandemic included New York, Boston, New Orleans, and Baltimore. Interestingly, these cities were also among the first to be affected by the deadly second wave of the virus. Communities that were not infected until later in the pandemic tended to have lower mortality rates.

By comparison, St. Louis made the decision to close its schools and ban public gatherings early in the pandemic. In the end, their peak mortality rate was merely one-eighth the peak mortality rate of Philadelphia. Gunnison, Colorado was another city that fared well during the pandemic after effectively shutting itself off from the world at the start of the pandemic.

Ultimately, the 1918 pandemic took the lives of 675,000 Americans. The true global statistics remain unknown, though conservative estimates range from 20 to 50 million. Some historians believe that number could be much higher.

The 1918 Pandemic in Cleveland, Ohio

Start of the Spanish Flu in Cleveland

On September 22, 1918, the city of Cleveland, Ohio issued its first official warning to citizens that the Spanish Flu had likely arrived in the city. Yet it was not until October 4 that the local government took action by directing City Health Commissioner Dr. Harry L. Rockwood to take a survey of the city’s influenza conditions and draft a precautionary plan of action. In retrospect, this delayed response may have triggered dire consequences for Cleveland’s population.

Dr. Rockwood’s plan outlined the need to isolate sick patients and prevent sick employees from reporting to work. Schools were asked to monitor students and send those with possible symptoms home. These measures were considered drastic at the time, but the Health Commissioner stressed that they were critical steps in preventing the spread of the disease.

Meanwhile, the Cleveland Police Department launched a “war on spitting” as yet another preventative measure. In alignment with this goal, the Cleveland Railway Company ordered its motormen to aid in the arrest of any passengers found spitting within their streetcars.

Despite these initial precautions, the number of positive Spanish Flu cases in Cleveland had grown to 500 by the end of the first week of October. What the city had deemed a distant threat just days earlier now seemed highly real and alarming.

A Rapidly Worsening Situation

In response, Dr. Rockwood formed an advisory board to draft new regulations for Cleveland businesses and employees. The board released a statement to residents explaining that it was their “patriotic duty to stay at home” if they began feeling ill. Business owners were asked to prevent seemingly-sick customers from entering their facilities. Still, the number of positive influenza cases grew day by day.

On October 15, at the urging of Health Commissioner Rockwood, the city of Cleveland ordered the closing of most public spaces, including schools, movie theaters, and churches. Weddings, funerals, and similar public gatherings were likewise prohibited.

Saloons and cabarets, however, were exempt from the order. These social establishments were not believed to be large enough gathering spaces to facilitate the spread of the virus. Additionally, many “banned” facilities such as theaters remained open in spite of the order.

Meanwhile, the Ohio Department of Health issued a statement recommending that local communities ban all large gatherings, but did not mandate any closures at the state level. Cleveland officials decided to maintain their current order, keeping saloons and bars open.

Just one day after Cleveland’s school system shut down, teachers were ordered to report back to their classrooms to aid nurses in investigating Spanish Flu cases among students. Upon finding that the number of cases was smaller than previously believed, the city announced that schools would reopen the following Monday.

However, this reopening never took place. In the span of several days, the rate of illness among students increased exponentially. Upon seeing this spike in influenza cases, the city decided the schools would remain closed.

Failure to Enforce Social Distancing

Across Cleveland, the ban on public gatherings was blatantly ignored by tens of thousands of citizens. Worshippers met in secret away from their churches and temples; business owners failed to regulate the number of patrons in their stores; residents carried on with their plans to meet and gather with friends.

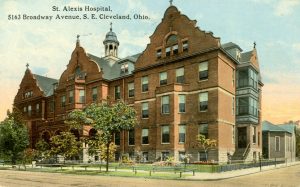

Cleveland Hospital, Source

By this point, Health Commissioner Rockwood had a sense of the devastation that would soon be coming to Cleveland. He estimated that roughly 1,000 hospital beds would be required within a matter of days, and asked the city for $105,000 to help prepare.

By October 21—less than one week after the ban on gatherings was announced—conditions in Cleveland were grim. The number of Spanish Flu cases in the city was nearing 7,000, and the 1,000 hospital beds ordered by Dr. Rockwood were already at capacity. It was clear that the number of new cases would soon outpace local hospitals’ ability to provide care.

In response, the Cleveland Normal School at University Circle was converted into a 100-bed hospital, and the Liberty Loan committee offered the use of its headquarters as a 20-bed annex for Grace Hospital (which still stands today as an acute long-term care facility). Over the next several days, regulations issued by Dr. Rockwood became more stringent. Office and store hours were restricted, and only essential services were allowed to operate past curfew. All open-air gatherings were outright prohibited.

Interesting Fact: The Normal School is no longer around, however it was located where the Cleveland School of the Arts stands today and across from Case Western Reserve University.

Cleveland normal School in 1910, Source

Business owners, churches, and citizens alike pushed back against these closures and regulations, and many people continued to disobey them. Yet the restrictions had still done their job: by the first week of November, the situation had improved enough in Cleveland for the city to begin lifting the bans in phases. On November 10, the closure order and gathering ban were both lifted completely, and schools were allowed to reopen later that week.

The Slow End of an Uphill Battle

The city quickly sprang back to life, and local bars, theaters and stadiums reopened to maximum-capacity crowds. Individual schools were required to close periodically over the coming months as absentee rates remained high due to student illness, but no new forced closures were issued by the city.

Yet this rapid return to normalcy did not come free of consequences. The citizens of Cleveland continued to fall prey to the Spanish Flu through the end of 1918 and into the next year. Between January and February 1919, an additional 800 deaths occurred in Cleveland. Nationally, a third wave of the Spanish Flu killed thousands more during spring of 1919.

Ultimately, more than 23,644 people became infected and over 4,400 people lost their lives in Cleveland during the 1918 pandemic—a mortality rate of roughly 18%. The city lost more of its citizens to the Spanish Flu than it did to the first World War.

1918 Pandemic vs. COVID-19 Pandemic

Unfortunately, the lessons learned during the 1918 pandemic faded quickly from public memory. Some historians believe this was due to the relatively short timeline of the pandemic; the majority of victims were killed within a span of just nine months. Other experts theorize that the media focus on World War I overshadowed Spanish Flu reports, causing it to become the “forgotten pandemic.”

As our city, state, nation, and planet continue to battle the coronavirus pandemic, it’s more important than ever to remember these lessons from history. Thus far, it seems that we have: the Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Amy Acton recently shared the state’s projected COVID-19 curve, which shows a peak of 6,000-8,000 new cases per day by late April.

Without social distancing measures put into place by the state of Ohio, this projection could have been as high as 40,000 new cases per day. These numbers would have surely overwhelmed healthcare facilities in Cleveland, just as local hospitals were overwhelmed by the Spanish Flu in 1918.

The events of 1918 paint a powerful picture about the importance of physical isolation and social distancing during a pandemic. When little is known about how to manage or treat an illness, preventing its spread is the most valuable life-saving tool at our disposal.

The Power of the Internet During COVID-19

There are some interesting differences between the COVID-19 pandemic and the Spanish Flu outbreak from a commercial real estate perspective as well—all of which we owe to the internet. For one thing, restaurants and retail stores are not outright closed today, as they were in 1918; they remain open for delivery and curbside pickup of online orders.

The same can be said of schools and offices. Today, millions of Americans are working and learning from home thanks to modern technologies such as the internet, VPNs, and databases. We can stream movies and music from the comfort of our living rooms, even as movie theaters and entertainment venues across the nation close their doors.

American manufacturers are aiding the U.S. response to COVID-19 in a way that was simply not possible in 1918. Hundreds of manufacturing companies have shifted gears to begin producing essential products like face shields and masks, hand sanitizer, and ventilators. Once again, we owe this good news to our ability to transmit information around the globe in an instant.

Many local businesses in Greater Cleveland are continuing to operate remotely, relying on tools like email, text messaging, and FaceTime to communicate with their customers. Here at CRESCO, we are offering virtual showings of commercial properties in order to continue serving our customers’ needs during these uncertain times.

In some ways, all of this can cause us to feel as if we’ve come to a standstill. With businesses remaining open and trying to adapt to this “new normal” of operating virtually, citizens and companies alike are left wondering when things will return to the way they were before. The good news? Even as we continue this game of “wait and see,” we have much to be thankful for when comparing our current situation to 1918.

Overall, regulations are much stricter today than they were a century ago—and that is an exceedingly good thing. We also have the power of modern technologies behind us. Armed with the protective measures that have been put into place and the cooperation of our citizens, we have every reason to be hopeful for a better outcome in 2020.

We wish all of our readers good health and good fortune during these difficult times. We look forward to emerging from this crisis to a Cleveland that is stronger and more united than ever.

To learn more about how CRESCO, Greater Cleveland’s leading commercial real estate company, can help you with your property needs, contact us at 216.520.1200, or fill out the form below. A CRESCO professional will contact you shortly.